How did Porsche make the OEM cabrio exhaust louder than the coupe?

#1

Racer

Thread Starter

Reading Rany Leffingwell's magnificent book "70 years Porsche - There Is No Substitute", it is mentioned that the 997 has a louder exhaust note than the coupe.

I also found the same quote in his book "The Complete Book of Porsche 911: Every Model Since 1964":

Because the roofline could not exactly mimic the coupe’s, engineers tweaked rear spoiler performance. It rose 20 milimeters (0.80 inches) higher than on the coupe to provide more aerodynamic effect. The subtly higher wing was not the only effect that top-down Porsche drivers noticed. “The exhaust sound was even more aggressive with the cabrio,” Bernd Kahnau explained with a broad grin. “Because of the open cabin, we wanted our customers to really be able to hear the engine.”

This had me puzzled.

Does anyone know how exactly they achieved this? Is there less dampening in the cab's mufflers, is the design of the exhaust different,...?

I have never heard that the coupe's and the cab's exhaust would not be interchangeable, so this would seem strange...

And does it apply only to the PSE exhausts or also the non-PSE ones?

Anyway, it is another reason to opt for a convertible. The whole driving experience is enhanced in every respect compared to a fixed roof 997

I also found the same quote in his book "The Complete Book of Porsche 911: Every Model Since 1964":

Because the roofline could not exactly mimic the coupe’s, engineers tweaked rear spoiler performance. It rose 20 milimeters (0.80 inches) higher than on the coupe to provide more aerodynamic effect. The subtly higher wing was not the only effect that top-down Porsche drivers noticed. “The exhaust sound was even more aggressive with the cabrio,” Bernd Kahnau explained with a broad grin. “Because of the open cabin, we wanted our customers to really be able to hear the engine.”

This had me puzzled.

Does anyone know how exactly they achieved this? Is there less dampening in the cab's mufflers, is the design of the exhaust different,...?

I have never heard that the coupe's and the cab's exhaust would not be interchangeable, so this would seem strange...

And does it apply only to the PSE exhausts or also the non-PSE ones?

Anyway, it is another reason to opt for a convertible. The whole driving experience is enhanced in every respect compared to a fixed roof 997

#2

I doubt that there is any difference in the mufflers. It doesn't make sense to do that from a cost perspective. I would suspect it's the cloth top and open cockpit that gives the allusion of a louder exhaust note.

Cw

Cw

#4

Racer

Thread Starter

#6

RL Community Team

Rennlist Member

Rennlist Member

Reading Rany Leffingwell's magnificent book "70 years Porsche - There Is No Substitute", it is mentioned that the 997 has a louder exhaust note than the coupe.

I also found the same quote in his book "The Complete Book of Porsche 911: Every Model Since 1964":

Because the roofline could not exactly mimic the coupe’s, engineers tweaked rear spoiler performance. It rose 20 milimeters (0.80 inches) higher than on the coupe to provide more aerodynamic effect. The subtly higher wing was not the only effect that top-down Porsche drivers noticed. “The exhaust sound was even more aggressive with the cabrio,” Bernd Kahnau explained with a broad grin. “Because of the open cabin, we wanted our customers to really be able to hear the engine.”

This had me puzzled.

Does anyone know how exactly they achieved this? Is there less dampening in the cab's mufflers, is the design of the exhaust different,...?

I have never heard that the coupe's and the cab's exhaust would not be interchangeable, so this would seem strange...

And does it apply only to the PSE exhausts or also the non-PSE ones?

Anyway, it is another reason to opt for a convertible. The whole driving experience is enhanced in every respect compared to a fixed roof 997

I also found the same quote in his book "The Complete Book of Porsche 911: Every Model Since 1964":

Because the roofline could not exactly mimic the coupe’s, engineers tweaked rear spoiler performance. It rose 20 milimeters (0.80 inches) higher than on the coupe to provide more aerodynamic effect. The subtly higher wing was not the only effect that top-down Porsche drivers noticed. “The exhaust sound was even more aggressive with the cabrio,” Bernd Kahnau explained with a broad grin. “Because of the open cabin, we wanted our customers to really be able to hear the engine.”

This had me puzzled.

Does anyone know how exactly they achieved this? Is there less dampening in the cab's mufflers, is the design of the exhaust different,...?

I have never heard that the coupe's and the cab's exhaust would not be interchangeable, so this would seem strange...

And does it apply only to the PSE exhausts or also the non-PSE ones?

Anyway, it is another reason to opt for a convertible. The whole driving experience is enhanced in every respect compared to a fixed roof 997

.

- "The exhaust sound was even more aggressive with the cabrio,” - That's an ambiguous phrase, but one interpretation of it is that Cabrios simply sound different (e.g. top down) and not that the exhaust system is physically different

- “Because of the open cabin, we wanted our customers to really be able to hear the engine." - Contextually that supports the open top interpretation of the above phrase

I had a brief glance at the US version and there's doesn't seem to be any difference in the exhaust part numbers for Cabrios. But if you're curious, you can dig through Katalog/PET in more detail and see if you can uncover something.

And if you do, please let us know.

Karl.

Last edited by wjk_glynn; 03-19-2019 at 04:45 PM.

#7

Racer

Thread Starter

The sentence you quoted doesn't necessarily mean there's a physically different exhaust on the Cabrios. Let's breakdown that sentence:

.

I had a brief glance at the US version and there's doesn't seem to be any difference in the exhaust part numbers for Cabrios. But if you're curious, you can dig through Katalog/PET in more detail and see if you can uncover something.

And if you do, please let us know.

Karl.

.

- "The exhaust sound was even more aggressive with the cabrio,” - That's an ambiguous phrase, but one interpretation of it is that Cabrios simply sound different (e.g. top down) and not that the exhaust system is physically different

- “Because of the open cabin, we wanted our customers to really be able to hear the engine." - Contextually that supports the open top interpretation of the above phrase

I had a brief glance at the US version and there's doesn't seem to be any difference in the exhaust part numbers for Cabrios. But if you're curious, you can dig through Katalog/PET in more detail and see if you can uncover something.

And if you do, please let us know.

Karl.

I checked the German parts catalogue, and didn't see any exhaust parts specific to the cabrio. I just makes a distinction between the M96/M97 and X51.

So your conclusion must be the right one.

The thing that threw me off was the guy saying "we wanted our customers to really be able to hear the engine", which to me seemed to imply that they undertook some kind of action to bring that effect about in the cabrio.

Trending Topics

#8

Poseur

Rennlist Member

Rennlist Member

Randy Leffingwell is a neighbor and friend, so I put the question up to him.

Randy reported to me that "...Essentially what Kahnau’s engineers did was turn the rear bulkhead into a kind of woofer using a device they discovered from a local Stuttgart company. Those guys called it a Sound Symposer and that is how Kahnau always referred to it.Think of a hollow metal tube physically attached to the engine case and to the rear bulkhead. There’s an awful lot more than that to it, but that’s the concept."

From his days reporting on the 'new' 997 in 2005:

Porsche’s New 997 Cabriolet

Written and Photographed by Randy Leffingwell

“The main product of this new line, the leadmodel of the 997, was the convertible,” August Achleitner said, “and not the coupe.” Achleitner is Porsche’s Director of Product Line Management for the Carrera. He was responsible for new vehicle concepts and packaging for all Porsche vehicles from 1989 through 2000. The 997 was largely his creation. “We didn’t talk about this, but now you know it.” He paused to look out of the windows of his first floor office in the Research & Design Center at Weissach. A daylong storm swirled snow down onto the already white ground. The temperature hung just below freezing. In Germany, late January is not convertible weather. But the factory already was turning out the soft top cars at the rate of two convertibles to every three coupes.

“This strategy came from the engineers’ point of view. The convertible is the more difficult car because of the stiffness that is necessary. Your work is easier when you consider some of these special parts, some of the reinforcements right from the beginning.” In the past, Porsche had made its coupes first and then, after they were finished, engineers started on open cars. With the 997, Achleitner’s team developed both simultaneously.

One month later, in mid-February, the story had moved to Seville, Spain. Wolfgang Dürheimer, Porsche’s vice president for research and development, had joined Porsche Presse staff and other engineers to assist the media launch of the new open car. The temperature touched 70 degrees at midday and the skies filled with sunlight unencumbered by clouds. It was convertible weather. As warm breezes brushed past a dozen brightly colored cabrios parked 100 meters away, Dürheimer explained the advantages the 997 had derived from Achleitner’s simultaneous effort. Developing the cabrios had provided Weissach’s engineers some unexpected benefits as they worked through what they refer to as “target conflicts.” These are the good-new-bad-news dilemmas that arise as one decision reveals two or three more questions, challenges, or choices.

“It was clear for us, right from the beginning, that we will have a coupe and a convertible. That was more or less the same with the 996. But this time we did it in a very concentrated fashion. So all the derivatives that the 997 will see, the Targa, the all-wheel-drives, the various GT models and others, all these we took into consideration right from the beginning.

“It makes life a bit harder to consider all these variants from the start. But it makes things easier at the end. It’s classical front loading. It takes a little bit more time thinking about things before you can weld the first parts. But some of what we tried to improve on the cabriolet brought us some very good aspects on the coupe as well.”

Dürheimer is fit and energetic. When he is not talking about Porsche’s projects, he recalls a helicopter skiing trip to Alaska a year ago this same week with three engineering colleagues from Weissach. On one day, they did twelve runs. For him, life and work are a blend of controlled high-speed experience, motion, and maneuverability.

“As you can imagine, to make a coupe quite stiff is not too difficult because you have a closed car with a roof. But if you want to have a stiff body on a cabriolet, it’s a little bit more difficult. We initiated this so-called third load path in terms of passive safety. It’s an upper load path that can take forces of an accident through the upper door section into the back of the car.”

This new “load-path” relies on a strong beam inside the sheet metal that extends across the top of each door, at the base of the A-pillar at the instrument panel. When Porsche drivers open the door, they will see a three-corner aluminum piece in the B-pillar. This is the point at which the door beam connects, making a very rigid torsional-, bending-, and stiffness-load passage from the front fenders to the rear of the car. One of its purposes is passenger compartment integrity in a front, side, or rear end crash. It will keep the compartment from folding in on itself as can happen in other open cars in high speed accidents. Its everyday benefit is in providing the new 997 cabriolet with five percent greater torsional stiffness and nine percent more flexing stiffness than the 996 cabrio.

“This system helped the coupe a lot even though it has a roof,” Dürheimer continued, “because the body along the window sill line got the same very strong reinforcement. This was an idea we had at the very beginning, thinking about the convertible and how we can make it more rigid. This is the profit of making the cabriolet and the coupe at the same time.”

The 911 presents a hard legacy to follow up. Its heritage offers as many challenges as it provides guidelines. For more than 40 years now, Porsche has produced this two-door automobile. Its characteristic front fenders still retain a form that, as Professor Porsche first dictated to Erwin Komenda, allows the driver to see where the front wheels are located. The 911 carries on Butzi Porsche’s iconic angled-down roof line. It still defines itself with the rear engine that has dictated the car’s shape, its form, its handling, its sound, and its appeal.

“This is a passion we follow,” Dürheimer went on. “If you get the chance to work on the 911, on the one hand this is a very big opportunity and on the other hand, it’s an obligation. The team is very aware of this. The health of the company is affected. Many jobs are at stake. Therefore everybody tries as hard as possible to get his component, his part, into the target section. We have many engineers at Weissach that make their application to Porsche after they are finished with their university degree. They get hired and they stay at Porsche all during their career, as long as they are engineers. They are deeply into their subjects, aerodynamics, acoustics, basic engine work, and they are constantly asking themselves, ‘What can I improve?’”

They fill notebooks and desk drawers with ideas, and when they get the next chance, they are ready. They pull out their wish lists. Dürheimer chides them: “Don’t stop making new suggestions. If you are not successful in bringing it into the present project, bring it next time. Do not abandon it.” One idea that his engineers brought back to the tables for the 997 was P.A.S.M., Porsche’s automatic stability management system.

“We tried PASM for the 996,” Bernd Kahnau said. Kahnau was project manager for 997, and served the same role for 996 and 993. He grew up inside Porsche, literally. His father was production manager in the 1950s and Kahnau’s earliest technical education came in the back seats of 356s. “But this system now is special for us. Bilstein built it. The Jaguar system back then was too soft and that was all that was available. It was too soon. The technology wasn’t ready for what we wanted the 996 to be able to do.”

Porsche’s ambitions were bold. For August Achleitner, the standard suspension always represented a compromise, even under the best of circumstances. At the beginning of the conceptual work on their new 911 in late 1998 and early 1999, Achleitner and his team of 20 engineers and designers had to decide what the new car would look like, how it would be equipped, how much horsepower it would have, and dozens of other questions and variables. They didn’t rely only on their own instincts but they also queried 993 and 996 owners as well as some individuals they located who had test-driven a 996 or a 993 but not bought one.

“One thing we noticed was that, for some people, the 996 was a little too soft at that time,” Achleitner explained. “We had no GT3 yet, no Turbo, no C4S. We knew what was coming in the future but we took this feedback from the market and decided that the 997 should be a little more muscular, a little bit sportier. But not too sporty, not too muscular, because we didn’t want to lose all the customers we had gotten from Mercedes-Benz and BMW. These are people who never would have bought a Porsche before. The 993, for example, had been too harsh, or too loud, or too uncomfortable for them.

“Then we had the question of how could we solve this task? You have to think about what makes a car faster, and, on the other hand, what can make the car smoother, more comfortable, without losing sportiness? One thing that came out of this target conflict was the PASM system for the 997. Except for the 959 which really was a prototype car, this 997 is the first time that we have offered an electronic spring and damper system.” (In the cabrio, this is an industry first.)

“At the beginning of the development, the target to make the car comfortable wasn’t so hard because we didn’t see a chance to make the car better than the 996. But especially within the last year of our work we learned a lot about what was possible with the software. Even our specialists only understood all the possibilities of this system within the last four of five months, just before the start of production. We could make tiny changes, even to accommodating a single bump in a smooth road.”

What PASM and their laptop computers allowed the engineers to do was fine tune characteristics that made any one Carrera S model (on which this suspension system is standard equipment,) into any of a variety of cars. As Wolfgang Dürheimer characterized it, “We have made it possible that two demands which could not be fulfilled in one car in the past could be covered with one new suspension system. It’s very sporty on one side. We can make our ‘Top Guns’ very happy and still bring them on a long distance trip from A to B and get them out of the car relaxed and ready for their next appointment.”

If their appointment is around Nurburgring’s Nordschlieffe, they will arrive a little earlier. “In comparison to the standard set up of the 996, the new 911, with its PASM in the ‘sports’ switch improved the lap time by 17 seconds,” Dürheimer said. “Seventeen seconds! In the past we were happy if we could find three seconds.”

For the cabrio this capability redefined what was possible with an open car. Even as Achleitner’s engineers replaced the front springs with those 10 percent softer, they substituted the rear suspension bushings with those much harder. Then his staff compressed the range of variability within the PASM to fit the cabriolet’s slightly diminished stiffness and the anticipated character of most cabrio drivers. In its stiffest “sport” settings, it comes up just about 15 percent softer than the calibration on the coupe, while the softest point is another couple of percent softer than the coupe.

All this may sound too badly compromised for the latent racer who might be contemplating an open 911. Still, it’s important to consider what two veteran racers said about the car after their long drives over one of Spain’s more tightly knotted mountain passes on the A-531. This is a smooth but narrow road that alternately wriggles and runs south from Seville toward Cadiz.

“Today was the first time I’ve driven the cabrio over this road,” Walter Rohrl said. “I’ve used this road for several days five years ago when we introduced the 996 Turbo here. This new car is very good. I drove it very fast, and its turn-in was excellent. Very precise. As good as the coupe. There were a number of very tight turns that I took at very high speeds in second and third gear and the car went exactly where I pointed it.”

Paul Frère, a man with an even longer experience racing Porsches than Rohrl’s spectacular career, sat across the dinner table from him at Seville’s legendaryEgana Orizarestaurant. Frère nodded appreciatively.

“You know,” he said, “it’s a very good car. I drove it hard and over some very bad roads. It’s very stiff, surprising for a cabrio, and there was no cowl shake at all. It’s a really good car. But, of course, I still prefer a coupe” Between the coupe and cabriolet, the PASM adjustments may read like a substantial character change on paper. On real roads, they’re barely noticeable to two experienced drivers.

Horsepower and torque ratings carry over directly from coupes to cabriolets, with the base car’s 3.6 liter flat six developing 273 lb-ft torque at 4250 rpm, and 325 brake horsepower at 6800 rpm. Likewise, the Carrera S pumps out 355 brake horsepower in either open or closed form at 6600 rpm and 295 lb-ft torque at 4600. These engines enable the S to accelerate from 0 to 100km/h in 4.9 seconds (one-tenth second longer than the coupe,) while the Carrera reaches the same speed in 5.2. Porsche’s quoted top speeds are 177 for the Carrera and 182 miles per hour for the Carrera S, down just one mile per hour from the coupe version. The S cabriolet weighs 3,318 pounds, while the standard Carrera is 55 pounds lighter at 3,263, without fluids.

Engineers are not the only ones at Weissach whom Wolfgang Dürheimer encourages to think ahead and develop ideas. Porsche’s design staff points its telescopes five and even ten years into the future. While Pinky Lai was slaving over ways to make the 996 form aerodynamically effective without the benefits of a movable wing, Grant Larson created the 986 Boxster alongside Lai in the same studio. As Lai developed the forms for Porsche’s 1999 Carrera, Larson began conceiving his own ideas for the next 911. When design chief Harm Lagaay put Larson and Mathias Kulla to work on the 997, their concepts did not just materialize from thin air.

“This is what’s important to understand,” Larson explained. “If you go to any one designer within the department, you can say, ‘Do a new 911.’ It’s not, really nota case where ideas have to just pop into our mind. That we have to start coming up with new ideas from nowhere. Forget it. We’ve got it in our head already. So when the word comes, we don’t just sit there and spend two years sketching around on it. We put down this idea that we’ve been thinking about the whole time the department was working on the previous generation.”

For Larson and Kulla, the legacy of the Porsche Cabriolet goes back generations. Butzi Porsche designed a version in the early 1960s that never left the design studio for a number of reasons. When the production version appeared in 1983, it was part of a larger strategy. Peter Schutz and Dr. Helmuth Bott used it to make the statement that, despite rumors of its demise, the 911 was alive and well. The 1983 cabrio surely was lively, but none of Porsche’s current staff of designers thought it looked very well.

Porsche carried over the same convertible roof from the 3.2 Carreras to the 964 series. “The first ones were more functional,” Grant Larson explained. “I think that’s the best way to describe it.” On the 993, designer Tony Hatter got a chance to tackle the roof, to smooth its shape, a task that he has called a “tricky business.” For Hatter, the classical 911 shape always was the coupe. But from his efforts came Lai’s forms with the 996 and now Larson’s with the 997.

“From generation to generation,” Larson said, “they’ve gained so much experience. There are new geometries and things they can work out. We have a lot of magnesium in the new roof. That makes it a lot lighter. We have a new ‘Z’ folding mechanism that made a whole lot more sense for the 996 and 997 versions. Those early cabriolet roofs took a whole lot of weight and pushed it back further where it shouldn’t be on the car. I’m involved heavily in this area of advanced design in cabriolet tops. One of our projects is roof systems, which is a very important consideration for our car, especially when you consider how many open 911s we sell.”

According to Dürheimer and 997 project manager Bernd Kahnau, 40 percent of all 997s will be cabriolets, and they intend to steer about 50 percent of those to the United States. The solid, fixed-glass back window with an electric defogger is just one of its bragging points. Now, at speeds up to 31 miles per hour, the Porsche driver can raise or lower the roof. That process, including dropping and raising side windows, takes just 20 seconds in either direction.

“There are a couple of parts that work really well with this car, not only the ‘moving while it’s driving’ function in the case of the 997’s convertible top,” Larson continued. “But it’s also important to think about how the top folds into the car without constricting the amount of luggage space. Any car can have a really fantastic system but it may eat up half the trunk. Our philosophy is to stick with a cabriolet roof, not only for reasons of tradition, but also for the considerations of purity, and sportiness, and light weight. That’s the reason we’re keeping folding roofs rather than going to a folding hardtop. If you added a folding hardtop to the car, you’d put its handling characteristics a little bit in jeopardy with all that added weight on top of the engine. And I don’t think our customers are out there screaming for a hard roof. And if they are, we have a hard top.” Unlike the 996, however, the convertible hardtop no longer is standard equipment on the new 997. Weighing 73 pounds, it’s an option selling for $2,345. “So many of the U.S. customers left them at the dealers, or never even picked them up,” Larson explained. “They all say, ‘I bought a cabriolet, not a coupe.’”

Porsche’s wholly-owned subsidiary CTS, Car Top Systems, developed the mechanism for the 997’s top and now manufactures the complete system with bows, hinges, motors, inner lining, glass, and outer material. They arrive from CTS fully assembled and, as does everything else on the Zuffenhausen assembly line, just in time for two men to lift it and set it onto the painted car body. Porsche offers it in black, grey, cocoa, and blue. The entire assembly weighs 42 kilograms, 93 pounds. But weight is always an enemy to Porsche engineers. While the cabriolet gained a total of 135 kilograms over the coupe, diligent management of every single system kept the net weight increase to just 85 kilograms, 187 pounds.

Because the roofline, even with Grant Larson’s efforts and CTS’s technology, cannot exactly mimic the coupes, August Achleitner’s engineers tweaked the performance of the rear spoiler. It rises 20 millimeters higher on the cabriolet than it does on the coupe to make it more aerodynamically effective. (Both coupe and cabriolets are identical height, 1310mm for the Carrera, 1300 for the S. However the cabrio’s higher rear wing impacts its Coefficient of Drag numbers. The coupes measure 0.28Cd while the cabrios come in at 0.29Cd.)

The subtly higher wing is not the only effect that top-down Porsche drivers may notice. As with the 996, audio volume increases or drops as road speed varies. But that’s just the beginning. No matter how the driver has adjusted graphic equalization and front-rear speaker balance on the standard Bose audio system, the open roof prompts the system to reconfigure the entire mix. Front-rear balance moves forward something like 20 centimeters, about 9 inches, and the system elevates bass and treble levels.

There’s another audio category in which American buyers benefit and open-car owners get even more. Because of this country’s relaxed exhaust-noise standards, U.S. buyers get the loudest exhausts of any 997 purchaser. “The exhaust sound is even more aggressive with the cabrio,” Bernd Kahnau explained with a broad grin, “because of the open cabin. We wanted our customers to really be able to hear the engine.” On the roads, that sound was familiar music to cabrio drivers’ ears. Whether in hard acceleration onto Spain’s Autovias or expressways, or in a pedal flat-to-the-floor naive attempt to follow Walter Rohrl, the engine and exhaust sounds reminded some drivers of the 993 more than a water-cooled 996. Bernd Kahnau knew the sound and explained the reason. “Our exhaust engineers? They are our Mozarts.”

Compared to the Carrera coupe at $69,300, and the Carrera S version at $79,100, the base Carrera cabriolet will list for $79,100 and the hotter Carrera S will post at $88,900. Cars are due in U.S. dealerships on March 12, 2005. Options include Porsche’s ceramic composite brakes (PCCB) at $8,150 for either model; the PASM for the base 3.6 liter Carrera at $1,990; and the Sports Chrono package for another $920. As with all current Porsche products, the company offers a far wider range of options that that make personal stylistic statements, available to discriminating customers by working with dealers and Porsche Exclusivat Zuffenhausen. Should you need music to accompany Bernd Kahnau’s exhaust note, CDs of Mozart, Motown, or Moby, are available locally.

© 2005 Randy Leffngwell All Rights Reserved.

Recall that for the Sport Exhaust sounds, it is attenuated between certain lower speeds. It was done to keep the Swiss happy--they have rather strict noise standards.

Randy reported to me that "...Essentially what Kahnau’s engineers did was turn the rear bulkhead into a kind of woofer using a device they discovered from a local Stuttgart company. Those guys called it a Sound Symposer and that is how Kahnau always referred to it.Think of a hollow metal tube physically attached to the engine case and to the rear bulkhead. There’s an awful lot more than that to it, but that’s the concept."

From his days reporting on the 'new' 997 in 2005:

Porsche’s New 997 Cabriolet

Written and Photographed by Randy Leffingwell

“The main product of this new line, the leadmodel of the 997, was the convertible,” August Achleitner said, “and not the coupe.” Achleitner is Porsche’s Director of Product Line Management for the Carrera. He was responsible for new vehicle concepts and packaging for all Porsche vehicles from 1989 through 2000. The 997 was largely his creation. “We didn’t talk about this, but now you know it.” He paused to look out of the windows of his first floor office in the Research & Design Center at Weissach. A daylong storm swirled snow down onto the already white ground. The temperature hung just below freezing. In Germany, late January is not convertible weather. But the factory already was turning out the soft top cars at the rate of two convertibles to every three coupes.

“This strategy came from the engineers’ point of view. The convertible is the more difficult car because of the stiffness that is necessary. Your work is easier when you consider some of these special parts, some of the reinforcements right from the beginning.” In the past, Porsche had made its coupes first and then, after they were finished, engineers started on open cars. With the 997, Achleitner’s team developed both simultaneously.

One month later, in mid-February, the story had moved to Seville, Spain. Wolfgang Dürheimer, Porsche’s vice president for research and development, had joined Porsche Presse staff and other engineers to assist the media launch of the new open car. The temperature touched 70 degrees at midday and the skies filled with sunlight unencumbered by clouds. It was convertible weather. As warm breezes brushed past a dozen brightly colored cabrios parked 100 meters away, Dürheimer explained the advantages the 997 had derived from Achleitner’s simultaneous effort. Developing the cabrios had provided Weissach’s engineers some unexpected benefits as they worked through what they refer to as “target conflicts.” These are the good-new-bad-news dilemmas that arise as one decision reveals two or three more questions, challenges, or choices.

“It was clear for us, right from the beginning, that we will have a coupe and a convertible. That was more or less the same with the 996. But this time we did it in a very concentrated fashion. So all the derivatives that the 997 will see, the Targa, the all-wheel-drives, the various GT models and others, all these we took into consideration right from the beginning.

“It makes life a bit harder to consider all these variants from the start. But it makes things easier at the end. It’s classical front loading. It takes a little bit more time thinking about things before you can weld the first parts. But some of what we tried to improve on the cabriolet brought us some very good aspects on the coupe as well.”

Dürheimer is fit and energetic. When he is not talking about Porsche’s projects, he recalls a helicopter skiing trip to Alaska a year ago this same week with three engineering colleagues from Weissach. On one day, they did twelve runs. For him, life and work are a blend of controlled high-speed experience, motion, and maneuverability.

“As you can imagine, to make a coupe quite stiff is not too difficult because you have a closed car with a roof. But if you want to have a stiff body on a cabriolet, it’s a little bit more difficult. We initiated this so-called third load path in terms of passive safety. It’s an upper load path that can take forces of an accident through the upper door section into the back of the car.”

This new “load-path” relies on a strong beam inside the sheet metal that extends across the top of each door, at the base of the A-pillar at the instrument panel. When Porsche drivers open the door, they will see a three-corner aluminum piece in the B-pillar. This is the point at which the door beam connects, making a very rigid torsional-, bending-, and stiffness-load passage from the front fenders to the rear of the car. One of its purposes is passenger compartment integrity in a front, side, or rear end crash. It will keep the compartment from folding in on itself as can happen in other open cars in high speed accidents. Its everyday benefit is in providing the new 997 cabriolet with five percent greater torsional stiffness and nine percent more flexing stiffness than the 996 cabrio.

“This system helped the coupe a lot even though it has a roof,” Dürheimer continued, “because the body along the window sill line got the same very strong reinforcement. This was an idea we had at the very beginning, thinking about the convertible and how we can make it more rigid. This is the profit of making the cabriolet and the coupe at the same time.”

The 911 presents a hard legacy to follow up. Its heritage offers as many challenges as it provides guidelines. For more than 40 years now, Porsche has produced this two-door automobile. Its characteristic front fenders still retain a form that, as Professor Porsche first dictated to Erwin Komenda, allows the driver to see where the front wheels are located. The 911 carries on Butzi Porsche’s iconic angled-down roof line. It still defines itself with the rear engine that has dictated the car’s shape, its form, its handling, its sound, and its appeal.

“This is a passion we follow,” Dürheimer went on. “If you get the chance to work on the 911, on the one hand this is a very big opportunity and on the other hand, it’s an obligation. The team is very aware of this. The health of the company is affected. Many jobs are at stake. Therefore everybody tries as hard as possible to get his component, his part, into the target section. We have many engineers at Weissach that make their application to Porsche after they are finished with their university degree. They get hired and they stay at Porsche all during their career, as long as they are engineers. They are deeply into their subjects, aerodynamics, acoustics, basic engine work, and they are constantly asking themselves, ‘What can I improve?’”

They fill notebooks and desk drawers with ideas, and when they get the next chance, they are ready. They pull out their wish lists. Dürheimer chides them: “Don’t stop making new suggestions. If you are not successful in bringing it into the present project, bring it next time. Do not abandon it.” One idea that his engineers brought back to the tables for the 997 was P.A.S.M., Porsche’s automatic stability management system.

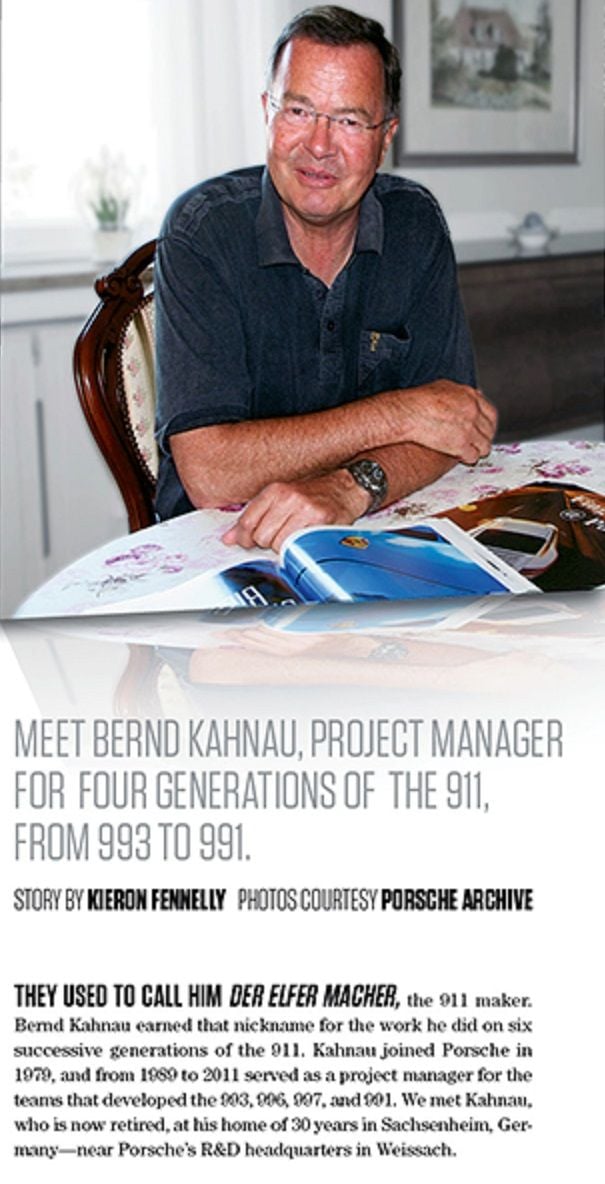

“We tried PASM for the 996,” Bernd Kahnau said. Kahnau was project manager for 997, and served the same role for 996 and 993. He grew up inside Porsche, literally. His father was production manager in the 1950s and Kahnau’s earliest technical education came in the back seats of 356s. “But this system now is special for us. Bilstein built it. The Jaguar system back then was too soft and that was all that was available. It was too soon. The technology wasn’t ready for what we wanted the 996 to be able to do.”

Porsche’s ambitions were bold. For August Achleitner, the standard suspension always represented a compromise, even under the best of circumstances. At the beginning of the conceptual work on their new 911 in late 1998 and early 1999, Achleitner and his team of 20 engineers and designers had to decide what the new car would look like, how it would be equipped, how much horsepower it would have, and dozens of other questions and variables. They didn’t rely only on their own instincts but they also queried 993 and 996 owners as well as some individuals they located who had test-driven a 996 or a 993 but not bought one.

“One thing we noticed was that, for some people, the 996 was a little too soft at that time,” Achleitner explained. “We had no GT3 yet, no Turbo, no C4S. We knew what was coming in the future but we took this feedback from the market and decided that the 997 should be a little more muscular, a little bit sportier. But not too sporty, not too muscular, because we didn’t want to lose all the customers we had gotten from Mercedes-Benz and BMW. These are people who never would have bought a Porsche before. The 993, for example, had been too harsh, or too loud, or too uncomfortable for them.

“Then we had the question of how could we solve this task? You have to think about what makes a car faster, and, on the other hand, what can make the car smoother, more comfortable, without losing sportiness? One thing that came out of this target conflict was the PASM system for the 997. Except for the 959 which really was a prototype car, this 997 is the first time that we have offered an electronic spring and damper system.” (In the cabrio, this is an industry first.)

“At the beginning of the development, the target to make the car comfortable wasn’t so hard because we didn’t see a chance to make the car better than the 996. But especially within the last year of our work we learned a lot about what was possible with the software. Even our specialists only understood all the possibilities of this system within the last four of five months, just before the start of production. We could make tiny changes, even to accommodating a single bump in a smooth road.”

What PASM and their laptop computers allowed the engineers to do was fine tune characteristics that made any one Carrera S model (on which this suspension system is standard equipment,) into any of a variety of cars. As Wolfgang Dürheimer characterized it, “We have made it possible that two demands which could not be fulfilled in one car in the past could be covered with one new suspension system. It’s very sporty on one side. We can make our ‘Top Guns’ very happy and still bring them on a long distance trip from A to B and get them out of the car relaxed and ready for their next appointment.”

If their appointment is around Nurburgring’s Nordschlieffe, they will arrive a little earlier. “In comparison to the standard set up of the 996, the new 911, with its PASM in the ‘sports’ switch improved the lap time by 17 seconds,” Dürheimer said. “Seventeen seconds! In the past we were happy if we could find three seconds.”

For the cabrio this capability redefined what was possible with an open car. Even as Achleitner’s engineers replaced the front springs with those 10 percent softer, they substituted the rear suspension bushings with those much harder. Then his staff compressed the range of variability within the PASM to fit the cabriolet’s slightly diminished stiffness and the anticipated character of most cabrio drivers. In its stiffest “sport” settings, it comes up just about 15 percent softer than the calibration on the coupe, while the softest point is another couple of percent softer than the coupe.

All this may sound too badly compromised for the latent racer who might be contemplating an open 911. Still, it’s important to consider what two veteran racers said about the car after their long drives over one of Spain’s more tightly knotted mountain passes on the A-531. This is a smooth but narrow road that alternately wriggles and runs south from Seville toward Cadiz.

“Today was the first time I’ve driven the cabrio over this road,” Walter Rohrl said. “I’ve used this road for several days five years ago when we introduced the 996 Turbo here. This new car is very good. I drove it very fast, and its turn-in was excellent. Very precise. As good as the coupe. There were a number of very tight turns that I took at very high speeds in second and third gear and the car went exactly where I pointed it.”

Paul Frère, a man with an even longer experience racing Porsches than Rohrl’s spectacular career, sat across the dinner table from him at Seville’s legendaryEgana Orizarestaurant. Frère nodded appreciatively.

“You know,” he said, “it’s a very good car. I drove it hard and over some very bad roads. It’s very stiff, surprising for a cabrio, and there was no cowl shake at all. It’s a really good car. But, of course, I still prefer a coupe” Between the coupe and cabriolet, the PASM adjustments may read like a substantial character change on paper. On real roads, they’re barely noticeable to two experienced drivers.

Horsepower and torque ratings carry over directly from coupes to cabriolets, with the base car’s 3.6 liter flat six developing 273 lb-ft torque at 4250 rpm, and 325 brake horsepower at 6800 rpm. Likewise, the Carrera S pumps out 355 brake horsepower in either open or closed form at 6600 rpm and 295 lb-ft torque at 4600. These engines enable the S to accelerate from 0 to 100km/h in 4.9 seconds (one-tenth second longer than the coupe,) while the Carrera reaches the same speed in 5.2. Porsche’s quoted top speeds are 177 for the Carrera and 182 miles per hour for the Carrera S, down just one mile per hour from the coupe version. The S cabriolet weighs 3,318 pounds, while the standard Carrera is 55 pounds lighter at 3,263, without fluids.

Engineers are not the only ones at Weissach whom Wolfgang Dürheimer encourages to think ahead and develop ideas. Porsche’s design staff points its telescopes five and even ten years into the future. While Pinky Lai was slaving over ways to make the 996 form aerodynamically effective without the benefits of a movable wing, Grant Larson created the 986 Boxster alongside Lai in the same studio. As Lai developed the forms for Porsche’s 1999 Carrera, Larson began conceiving his own ideas for the next 911. When design chief Harm Lagaay put Larson and Mathias Kulla to work on the 997, their concepts did not just materialize from thin air.

“This is what’s important to understand,” Larson explained. “If you go to any one designer within the department, you can say, ‘Do a new 911.’ It’s not, really nota case where ideas have to just pop into our mind. That we have to start coming up with new ideas from nowhere. Forget it. We’ve got it in our head already. So when the word comes, we don’t just sit there and spend two years sketching around on it. We put down this idea that we’ve been thinking about the whole time the department was working on the previous generation.”

For Larson and Kulla, the legacy of the Porsche Cabriolet goes back generations. Butzi Porsche designed a version in the early 1960s that never left the design studio for a number of reasons. When the production version appeared in 1983, it was part of a larger strategy. Peter Schutz and Dr. Helmuth Bott used it to make the statement that, despite rumors of its demise, the 911 was alive and well. The 1983 cabrio surely was lively, but none of Porsche’s current staff of designers thought it looked very well.

Porsche carried over the same convertible roof from the 3.2 Carreras to the 964 series. “The first ones were more functional,” Grant Larson explained. “I think that’s the best way to describe it.” On the 993, designer Tony Hatter got a chance to tackle the roof, to smooth its shape, a task that he has called a “tricky business.” For Hatter, the classical 911 shape always was the coupe. But from his efforts came Lai’s forms with the 996 and now Larson’s with the 997.

“From generation to generation,” Larson said, “they’ve gained so much experience. There are new geometries and things they can work out. We have a lot of magnesium in the new roof. That makes it a lot lighter. We have a new ‘Z’ folding mechanism that made a whole lot more sense for the 996 and 997 versions. Those early cabriolet roofs took a whole lot of weight and pushed it back further where it shouldn’t be on the car. I’m involved heavily in this area of advanced design in cabriolet tops. One of our projects is roof systems, which is a very important consideration for our car, especially when you consider how many open 911s we sell.”

According to Dürheimer and 997 project manager Bernd Kahnau, 40 percent of all 997s will be cabriolets, and they intend to steer about 50 percent of those to the United States. The solid, fixed-glass back window with an electric defogger is just one of its bragging points. Now, at speeds up to 31 miles per hour, the Porsche driver can raise or lower the roof. That process, including dropping and raising side windows, takes just 20 seconds in either direction.

“There are a couple of parts that work really well with this car, not only the ‘moving while it’s driving’ function in the case of the 997’s convertible top,” Larson continued. “But it’s also important to think about how the top folds into the car without constricting the amount of luggage space. Any car can have a really fantastic system but it may eat up half the trunk. Our philosophy is to stick with a cabriolet roof, not only for reasons of tradition, but also for the considerations of purity, and sportiness, and light weight. That’s the reason we’re keeping folding roofs rather than going to a folding hardtop. If you added a folding hardtop to the car, you’d put its handling characteristics a little bit in jeopardy with all that added weight on top of the engine. And I don’t think our customers are out there screaming for a hard roof. And if they are, we have a hard top.” Unlike the 996, however, the convertible hardtop no longer is standard equipment on the new 997. Weighing 73 pounds, it’s an option selling for $2,345. “So many of the U.S. customers left them at the dealers, or never even picked them up,” Larson explained. “They all say, ‘I bought a cabriolet, not a coupe.’”

Porsche’s wholly-owned subsidiary CTS, Car Top Systems, developed the mechanism for the 997’s top and now manufactures the complete system with bows, hinges, motors, inner lining, glass, and outer material. They arrive from CTS fully assembled and, as does everything else on the Zuffenhausen assembly line, just in time for two men to lift it and set it onto the painted car body. Porsche offers it in black, grey, cocoa, and blue. The entire assembly weighs 42 kilograms, 93 pounds. But weight is always an enemy to Porsche engineers. While the cabriolet gained a total of 135 kilograms over the coupe, diligent management of every single system kept the net weight increase to just 85 kilograms, 187 pounds.

Because the roofline, even with Grant Larson’s efforts and CTS’s technology, cannot exactly mimic the coupes, August Achleitner’s engineers tweaked the performance of the rear spoiler. It rises 20 millimeters higher on the cabriolet than it does on the coupe to make it more aerodynamically effective. (Both coupe and cabriolets are identical height, 1310mm for the Carrera, 1300 for the S. However the cabrio’s higher rear wing impacts its Coefficient of Drag numbers. The coupes measure 0.28Cd while the cabrios come in at 0.29Cd.)

The subtly higher wing is not the only effect that top-down Porsche drivers may notice. As with the 996, audio volume increases or drops as road speed varies. But that’s just the beginning. No matter how the driver has adjusted graphic equalization and front-rear speaker balance on the standard Bose audio system, the open roof prompts the system to reconfigure the entire mix. Front-rear balance moves forward something like 20 centimeters, about 9 inches, and the system elevates bass and treble levels.

There’s another audio category in which American buyers benefit and open-car owners get even more. Because of this country’s relaxed exhaust-noise standards, U.S. buyers get the loudest exhausts of any 997 purchaser. “The exhaust sound is even more aggressive with the cabrio,” Bernd Kahnau explained with a broad grin, “because of the open cabin. We wanted our customers to really be able to hear the engine.” On the roads, that sound was familiar music to cabrio drivers’ ears. Whether in hard acceleration onto Spain’s Autovias or expressways, or in a pedal flat-to-the-floor naive attempt to follow Walter Rohrl, the engine and exhaust sounds reminded some drivers of the 993 more than a water-cooled 996. Bernd Kahnau knew the sound and explained the reason. “Our exhaust engineers? They are our Mozarts.”

Compared to the Carrera coupe at $69,300, and the Carrera S version at $79,100, the base Carrera cabriolet will list for $79,100 and the hotter Carrera S will post at $88,900. Cars are due in U.S. dealerships on March 12, 2005. Options include Porsche’s ceramic composite brakes (PCCB) at $8,150 for either model; the PASM for the base 3.6 liter Carrera at $1,990; and the Sports Chrono package for another $920. As with all current Porsche products, the company offers a far wider range of options that that make personal stylistic statements, available to discriminating customers by working with dealers and Porsche Exclusivat Zuffenhausen. Should you need music to accompany Bernd Kahnau’s exhaust note, CDs of Mozart, Motown, or Moby, are available locally.

© 2005 Randy Leffngwell All Rights Reserved.

Recall that for the Sport Exhaust sounds, it is attenuated between certain lower speeds. It was done to keep the Swiss happy--they have rather strict noise standards.

#9

Racer

Thread Starter

I continue to be amazed by all the knowledge that is present on this fantastic forum

Randy reported to me that "...Essentially what Kahnau’s engineers did was turn the rear bulkhead into a kind of woofer using a device they discovered from a local Stuttgart company. Those guys called it a Sound Symposer and that is how Kahnau always referred to it.Think of a hollow metal tube physically attached to the engine case and to the rear bulkhead. There’s an awful lot more than that to it, but that’s the concept."

So I am still not sure whether the cab's aural advantage is the result of a deliberate engineering effort, or simply the result of open-top motoring in itself.

[...]

Recall that for the Sport Exhaust sounds, it is attenuated between certain lower speeds. It was done to keep the Swiss happy--they have rather strict noise standards.

Recall that for the Sport Exhaust sounds, it is attenuated between certain lower speeds. It was done to keep the Swiss happy--they have rather strict noise standards.

#10

This caught my eye because I thought my car had a decent sound that was a little louder than what guys on here describe their exhaust note to be. I know that it is very subjective, but I couldn't understand why everyone wanted louder. . I asked my indie when they replaced my clutch and he said the same thing, it sounds loud in a good way. All the parts look stock.

#11

Racer

Thread Starter

This caught my eye because I thought my car had a decent sound that was a little louder than what guys on here describe their exhaust note to be. I know that it is very subjective, but I couldn't understand why everyone wanted louder. . I asked my indie when they replaced my clutch and he said the same thing, it sounds loud in a good way. All the parts look stock.